Peacebuilding in Colombia: Lessons in Reconciliation

HU’s Corie Walsh reflects on what our Colombian partners have taught us about reconciliation, and how peacebuilding is an act of love.

HU’s Corie Walsh reflects on what our Colombian partners have taught us about reconciliation, and how peacebuilding is an act of love.

This is the second in a series of blogs on peacebuilding in Colombia. View the full series here.

In the wake of conflict, communities and governments must determine how to live in the muddy realities of harm, hurt, and reconciliation – and often against the backdrop of the involvement, perspectives, and interests of the international community and funders.

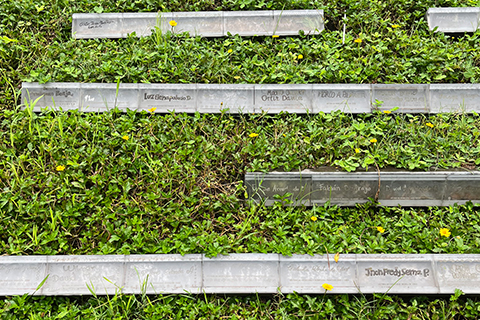

These complexities are highlighted in Colombia, which is six years out from the signing of a peace agreement and has recently launched a Truth Commission report that details the violence committed during the conflict. Citizens, individually and collectively, are committed to looking for a way forward for their country while accepting the difficult truth that they must live in community with those who did them harm.

Earlier this year a group of Humanity United colleagues spent two weeks in Colombia meeting with our partners and delving into the country’s ongoing peace process. This trip took place at a historic moment in Colombia’s history with the inauguration of a new president and the launch of the Truth Commission report.

The conflict formally ended in 2016 with the signing of the peace agreement between former President Juan Manuel Santos’ government and the people’s army, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), but in many ways the conflict is not over, especially for the communities most impacted. The rural and ethnic communities (a term used to refer to Afro-Colombians, Indigenous, and campesinos) still face violence. When the Truth Commission report was initially launched in D.C. this summer, an Afro-Colombian in diaspora came to the mic and asked, “How can the commission be ending? How can the report be complete? We are still facing violence every day. Have you forgotten about us?”

The Colombian Peace Agreement is the most comprehensive peace agreement in history and arguably the most state-owned (as opposed to Western international ownership). This agreement is thoroughly Colombian, designed and owned by the people. For this the people are incredibly proud. The international community is perceived as a steadfast supporter of the peace process as it has called attention to the process and prevented it from disappearing from the world’s view.

During our visit we engaged with partners at all levels of the peacebuilding system – from grassroots organizations to truth commissioners to former President Santos – and saw that at every level the conflict had a profound and far-reaching impact. We also saw an overwhelming sense of love, dignity, trust, and a fragile but persistent hope.

In Colombia, people have faced indescribable violence – sexual violence, disappearance, murder, land mines, arson, aggressive recruitment of children, and falsos positivos (false positives are instances where during the conflict the military would kill civilians and plant guerilla weapons on them to increase their head count).

Peacebuilding, as the Colombian context teaches us, is an act of love. Love in this case is a verb and a choice, when faced with complexity. We do not inhabit a work of black and white, where conflict is resolved neatly, heroes and villains are clearly delineated, and a best case scenario is a return to a stable status quo. Moving from a place of love, Colombians have asked how to build new realities, how to have accountability, and how to be in partnership with those who were once the enemy.

What we’ve learned from our partners is we must find ways to strike down what is harmful, what initially brought us to a point of violence, and then imagine new ways of being and find space for everyone.

In the 2016 referendum for the peace agreement, FARC narrowly lost the public vote. Those who voted against it were the upper middle class and urban who were ideologically opposed to coming to the table with FARC. Many of those most impacted by the violence were in favor of the agreement. We saw this reflected in the victims, the Truth Commission representatives, and the government officials we met with. Those most impacted by the violence have run toward transitional justice. They have accepted combatants getting amnesty, reintegrating into society and finding redemption. They consistently have said they are not seeking revenge because revenge will bring them nothing. Instead, what they are seeking is truth, because the truth of what happened to them and their loved ones will bring them peace. They are seeking justice, in the sense of creating a public truth about the realities of conflict and a record of what has occurred. They are also fervently hoping they can prevent this from ever happening again. They bear their pain in the hope of building a better future for those who come next.

As one youth activist put it during the formal launch of the Truth Commission Report in Bogotá, “This armed conflict has lost three generations. We refuse to become the fourth… We want to decentralize the truth and face the truth of the conflict to build a new future. This is our legacy and we do it with joy. Do not leave us alone with this legacy as we walk toward peace.”

Humanity United’s peacebuilding work is guided by the goal of building a transformed system focused on the agency, expertise, and power of local people who are in service of resilient peace. We see this beautifully represented across Colombia in concrete actions, in attitude, and in the value of local voice. Sadly, nuanced and locally-driven peace is not available to many countries and communities because of international oppression, power inequities, and the failings of the global peace system.

There are many contexts where the international community and disproportionately powerful western actors will not rally to create a stable pathway for peace. Instead these actors will assume superiority, inhibit progress in the name of economic and political interests, and exclude local voices from peace processes.

If the Colombian peace process and journey teaches us anything, it is the desperate need for critical reflection within the funding community of how we enable the conditions for peacebuilding led locally and led by love, instead of continuing to replicate the dynamics that create harm.

Corie Walsh is a Portfolio Manager for Peacebuilding at Humanity United.