This is a guest blog from Evelyn Chumbow and Fainess Lipenga from the Human Trafficking Legal Center (HTLC). Recently, HTLC conducted a survey for survivors of human trafficking on the impact of racism on their lives. In this piece, Evelyn and Fainess dive into the findings of that survey and share some of their own reflections on the role racism plays in the anti-human trafficking movement.

We are leaders in the anti-trafficking movement. We are also trafficking survivors. And we write this article to raise the alarm. The anti-trafficking movement must address issues of systemic racism.

In 2020, in the midst of the pandemic, a small group of trafficking survivors and the staff of the Human Trafficking Legal Center met (virtually) to discuss an upcoming panel discussion. One of us, Evelyn Chumbow, who serves on the Human Trafficking Legal Center’s Board of Directors, suggested that the panel focus on racism. The brainstorming that day ended with a decision to conduct a survey for human trafficking survivors.

The survey, developed by the survivors on the panel, included six yes/no questions, as well as an open-ended question that solicited comments from survey participants on the impact of racism in their lives. The survey was conducted in English, Spanish, Tagalog, Amharic, and Chinese between February 8 and February 28, 2021.

In all, 87 individuals who identified as survivors completed the survey. Of the 87 respondents who identified as trafficking survivors:

- 62 identified as people of color (74% of total respondents);

- 16 identified as white (19% of total respondents);

- 6 did not identify as any race.

The answers to the survey questions exposed deep concern about racism among trafficking survivors, especially among survivors who identified as People of Color.

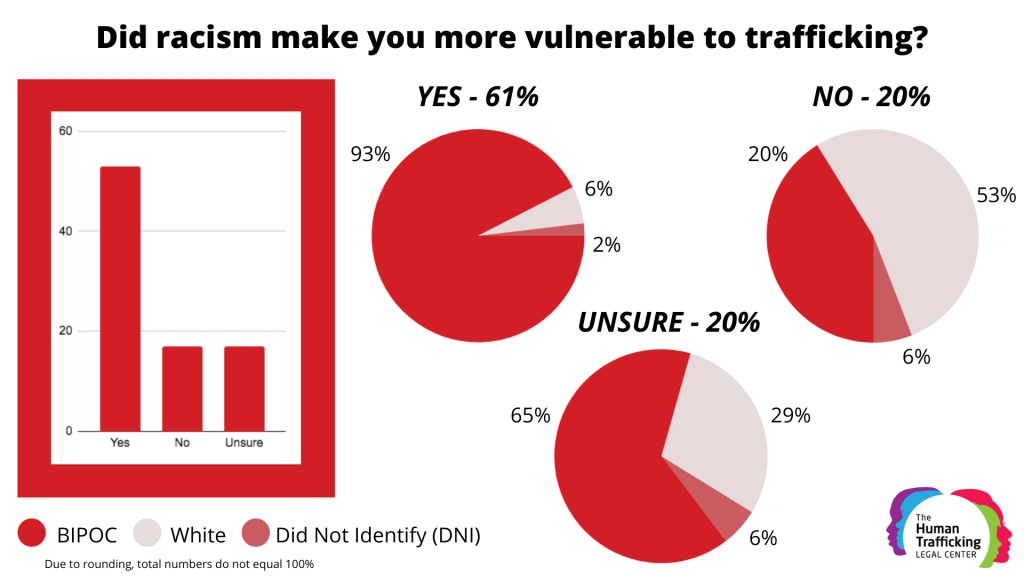

Of the people who answered yes to the question, “Did racism make you more vulnerable to trafficking?,” 93% identified as People of Color.

Of those who answered yes to the question, “Did racism make it more difficult for you to access services such as housing, case management, or legal representation?,” 92% identified as People of Color.

Of all the respondents who answered yes to the question, “Did racism make it more difficult for you to access healthcare?,” 90% identified as People of Color.

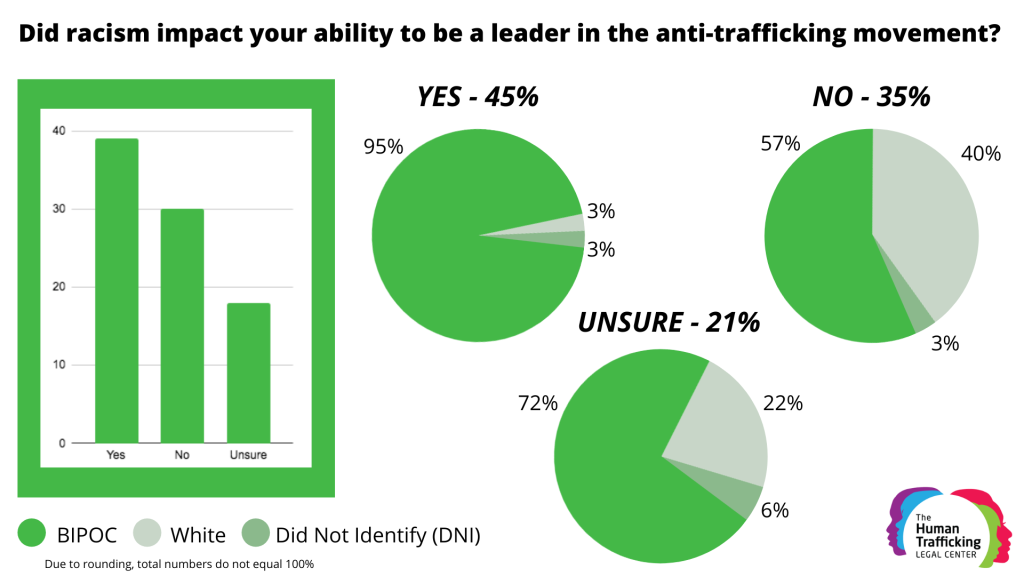

Of all the respondents who answered yes to the question, “Did racism impact your ability to be a leader in the anti-trafficking movement?,” 95% identified as People of Color.

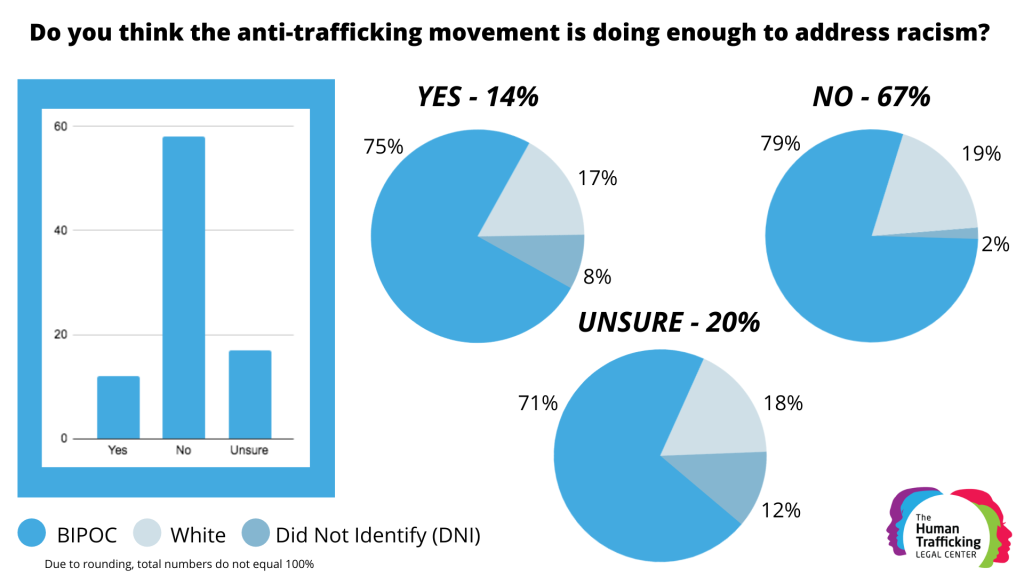

Only 14% of all respondents answered yes to the question, “Do you think the anti-trafficking movement is doing enough to address racism?” Of all the respondents who answered no, 79% identified as People of Color.

The survey results are clear: Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC) trafficking survivors feel that racism makes it more difficult for them to access services, more difficult to access housing, and more difficult to be a leader in the anti-trafficking movement. And just 14% of all respondents believe that the anti-trafficking movement is doing enough to address racism.

Even more compelling, the survey respondents shared their personal impressions:

- “Racist policies are the driving force behind the anti-trafficking movement.”

- “White survivors, knowing that racism exists, could be more generous in de-centering themselves so that BIPOC survivors can also have a seat at the table. They can also be advocate voices on behalf of BIPOC survivors with the larger anti-trafficking orgs who generally don’t consider our voices.”

- “When you look at survivor leaders, the white survivors get access to more opportunities while the black survivors are looked upon as the answer black girl.”

- “The anti-trafficking movement needs to do more to uplift black survivor voices. This means being more intentional in reaching out, mentoring, and providing support to Black survivors so they can develop the skills needed to move into leadership positions.”

- “The fact that we have these lived experiences receives a lot of stigma and makes it difficult for a survivor to be considered a professional. Also the movement needs to change the narrative to be more solution focused.”

We both experienced trafficking for forced labor here in the United States. We were both trafficked from Africa. We have both served in this movement for years. We have both experienced racism. It is impossible to remain silent.

The survey respondents’ statements underscore the racism that we see in the anti-trafficking movement. As we look around, we see that almost all the directors of human trafficking organizations are White. Black, Indigenous, People of Color have little representation in the organizations that dominate this movement. There is little diversity in the survivor-leaders who are chosen to advise and staff these organizations.

As survivors of color and immigrants, we are overlooked. When hiring survivor-leaders to do presentations or serve as consultants, organizations frequently pass over immigrant survivors in favor of native-English speakers. Some anti-trafficking NGOs discredit our work and skills due to language barriers, in addition to our race.

We also see instances in which non-profit organizations use survivors of color in their grant applications, or use them to raise money without their permission. These same groups then fail to involve the survivors of color in the work. Survivors of color are seen as inadequate to implement the projects with the organization, although they are used to obtain the funds. That is a huge disparity. It is also exploitation.

Labor trafficking survivors – many of whom are people of color and immigrants – face additional discrimination in the anti-trafficking movement. There are few resources or scholarships for labor trafficking survivors. In contrast, sex trafficking survivors have access to dedicated scholarships and other resources.

Racism is blatant when the Trump Administration, rather than invite a forced labor immigrant BIPOC survivor who works in Washington, DC to a White House meeting, instead flies a White sex trafficking survivor across the country to participate. And it is subtle when colleagues in the movement call to “pick your brain,” but, in the words of one survivor-leader of color, “Really only want to steal from you.”

This must change. Our motto is, “Nothing about us, without us.” Black, Indigenous, People of Color trafficking survivors must be included in decision-making in the anti-trafficking movement. Our voices must be heard. That is what this survey tells us. And that is what we know.

Evelyn Chumbow is a member of the Human Trafficking Legal Center’s Board of Directors. She formerly served on the U.S. Human Trafficking Advisory Council and currently serves on the Board of Directors of Free the Slaves. Fainess Lipenga is on the staff of the Human Trafficking Legal Center, where she serves as the Training Advisor. She is the recipient of the D.C. U.S. Attorney’s Office Justice for Victims of Crime Award and currently serves on the Board of Directors of Survivor Alliance.