Today, with support from Humanity United with funds from UK aid from the UK government, Social Finance released a report that explores whether an outcomes-based “smart subsidy” could help to shift norms in the sector and give workers more freedom and agency. This is a guest post from Olivia Hanrahan-Soar, Manager at Social Finance.

Register here for a webinar to discuss the findings of this report and its implications.

The Covid-19 crisis has shone a light on many underlying social problems across the world, including health inequalities, the prevalence of mental health issues, and inequities in job security. One issue which has been brought to the fore is the precarious position of migrant workers from low income countries, many of whom have found themselves trapped in host countries as businesses shuttered and lockdowns began.

In the news are reports of workers’ inability to return home from migrant labour hotspots like the Gulf and Southeast Asia; the lack of public provisions for foreign-born populations; clusters of infections among migrant workers housed in crowded dormitories; and the subsequent public and political backlash in some countries.

The stories are revealing, and sometimes heart-wrenching, but what are the underlying issues which have led migrants to this situation in the first place?

There are many reasons why someone would seek work in a foreign country: limited economic opportunities at home and a desire to send remittances home to family are primary drivers. However, many people, especially in remote areas of developing countries, don’t have ready access to employment abroad, meaning they are reliant on networks of intermediaries—recruitment agents—to help them find overseas work placements.

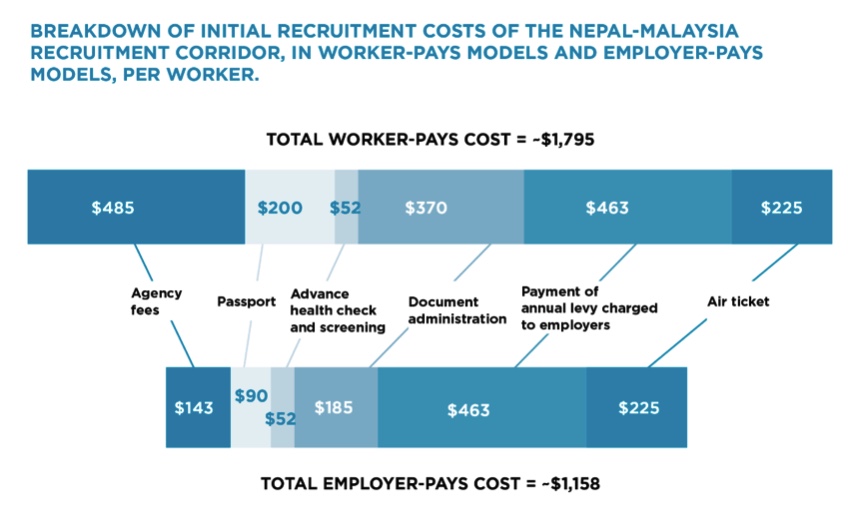

These recruiters often operate outside of the formal economy and are unregulated, and many charge extortionate fees in exchange for access to jobs. Social Finance’s analysis found that workers travelling from Nepal to Malaysia to work in the electronics industry were charged an average of US$ 1,795 for their jobs, which they had to pay in the form of loans. This debt increased to around $3,300 over the next two years as inflated interest rates, charged by moneylenders, were included. The toll of repaying this debt is such that, according to our analysis, a typical worker is limited to sending home just $300 over the course of two years.

Furthermore, once in in their host country, workers may find that the job differs from the one promised: perhaps the hours are different, or the pay, or the type of job entirely. By this point, however, the worker is in significant debt and has little choice but to remain: they become bonded to their jobs.

What are the drivers of bonded labour?

- On the supply side, workers may have no choice but to pay for jobs, and in most countries the recruitment market is dominated by large recruitment firms which entrench and normalize worker payments. They could charge employers instead, but employers typically pay recruiters less than workers do—on average, about $1,150 per job, according to our analysis. Employers also don’t pay up front, like workers do—meaning an employer-pays model has significant working-capital requirements for recruiters.

- On the demand side, where factories and suppliers to large multinational brands need workers, there is a cost incentive to continue allowing workers to subsidise their own jobs. Some brands make efforts to remedy the problem, requiring suppliers to pay for recruitment themselves and spot-checking factories to make sure this happens. Many brands say they shoulder the incremental cost through the price they pay for finished products or components. However, the size and complexity of supply chains means it is a gargantuan task to verify whether this is actually occurring.

To make a sustainable, meaningful impact on this issue, it needs to be tackled from both the supply and demand sides. A working supply side needs a working demand side and vice versa. A first step could be helping to build a viable market of ethical, employer-pays recruitment firms for multinational supply chains.

How can we incentivise the development of ethical recruitment firms?

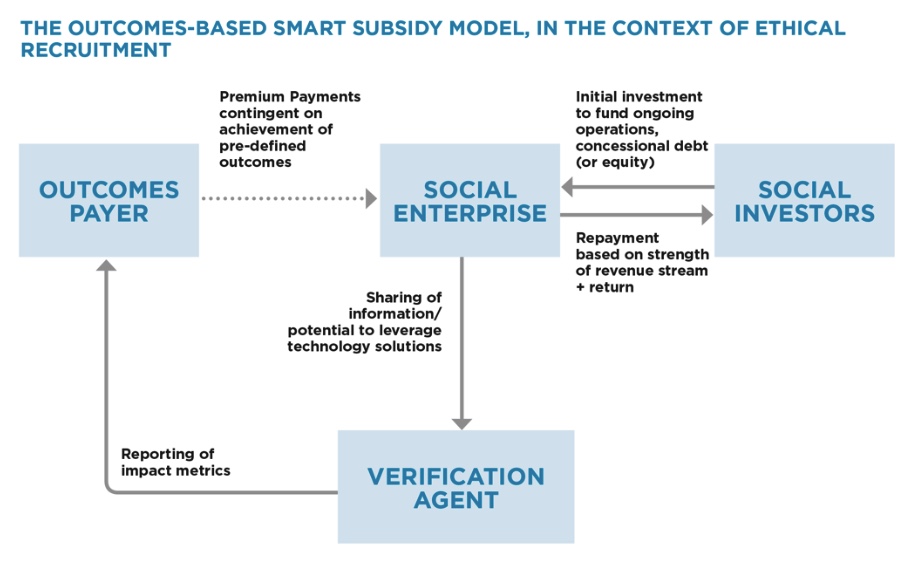

What if a “smart subsidy” were paid to recruitment firms who could prove that they had not charged workers fees? Workers placed by the recruiter could provide feedback—potentially via anonymised technology—on whether or not they had paid fees, and if it were confirmed that a recruiter had meaningfully shifted business models towards an “employer-pays” model, they would be eligible for outcomes payments. Working capital to enable this shift might be provided by social investors: together, the different revenue streams could help to grow the ethical recruitment market while ensuring a rigorous focus on quality.

What’s more, building a network of proven ethical recruitment firms would help smooth the demand side of the problem: brands would be able to easily connect their suppliers with local ethical recruiters, and enforcing suppliers’ compliance would be much simpler given the monitoring and verification built into the model.

When it comes to Covid-19, the current recognition of the importance of global migration and worker recruitment may offer an opportunity if we can take advantage of the moment of reflection to shift to a new normal once migration resumes and pent-up supply and demand for migrant labour begins to flow. With it, one can hope, fees for recruitment can begin to flow in the right direction.

—

Social Finance is a not for profit organization that partners with the government, social sector and financial community in the UK and beyond to find better ways of tackling social problems.